Are "Soft Landings" really softer?

Falling off a roof, I'd rather have a soft landing than a hard one; but, does the metaphor translate to economies?

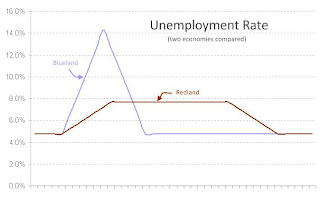

Example: Imagine two countries -- Redland and Blueland -- both with unemployment around 5%.

Next, imagine unemployment shoots up to 14% in "Blueland" while "Redland" has a far milder rise to 8%.

However, the rate of unemployment comes back to 5% much sooner in Blueland, while it lingers at a 8% for a while in Redland.

Is there any reason to think Redland is better off in this example? Even if we accept the notion that governments can and may engineer a soft-landing, it is far from clear that a shallower recession is a good thing, if it means extending its duration.

Think of individuals: Would you rather be unemployed for 1 year or for 3 years? It's a no-brainer! A laid-off dad from my son's school told me his savings could last him six months before he starts getting desperate. For him, a short sharp downturn would be softer. A worse rate of employment is the softer landing for the person who is unemployed, if it means a short unemployment. To some extent, those thinking about a soft-landing in the conventional way are committing a fallacy of composition.

Softer for some: The political support for soft-landings comes from those who think it will save their job or put them back to work. Imagine a company which is about to fire 10 employees due to budget cuts. Then, the government provides some type of aid and they only fire 5. The 5 who still have their jobs are pleased. Not just them: the 200 other employees in the company breathe more easily too.

Even the injured are positive: The 5 fired employees who will end up being out of work for longer -- because the wealth for the 5 "saved" jobs has to come from somewhere else -- are not pleased, but they often think positively about the soft-landing that "at least saved some jobs". Instead of being against soft-landings, they're the ones thinking the government ought to have done more. (If the government could work miracles by creating wealth out of thin air, why wouldn't they simply save each and every job lost anytime, anywhere.)

New reality: A bust happens when people around the economy change some very fundamental assumptions, and react to these changes. Finally, the economy will adjust to the new assumptions. Generally, the faster the adjustment, the better.

Panic vs. Adjustment: Even so, there is an argument for soft-landings which must be addressed. This is an economic argument that can be called "panic vs. adjustment", and it goes like this: it is true that the economy has to adjust and the sooner the better, but if this happens in a state of panic, it causes additional more damage. Take the example from above, of a company that was going to lay off 10 employees, but the government "saves 5 jobs". The argument would be made as follows: the panic has sent things below the point where they're finally going to end up. If the company fires 10 employees today, in a year or two -- when things are stable -- they will want to hire back 5. Why fire those 5 employees today and risk having them shift to some other occupation; then, hire 5 others employees in a year or two?

Vulture investors: There's an element of plausibility to the premises of that argument. Emotions run high in booms and in busts. Yet, in every boom, there are also some investors who hold back when they think optimism has run too high. During a bust, these people are happy to step in and put money into areas that they think are going cheap. Even a bankrupt company often has investors ready to pick up the pieces. In fact, since bankruptcy removes various legal obligations to pay its debts, a failing company becomes more attractive to buyers once it has gone through bankruptcy.

The government often touts the GM turnaround as a success, but it is no such thing. When governments attempt rescues, their eyes are on votes rather than profitability. GM would not have disappeared in a bankruptcy. Instead, it would have been owned by people who were formerly its creditors. Relieved of debt, the new owners would have invested in their assets. Instead, the government virtually ripped up the creditors' contract and gave the unions concessions. In doing so, they gained votes, but ended up with a company that is saved for now, but weaker than it would have been post-bankruptcy. By robbing the creditors, the government also makes it more costly for similar firms to borrow from creditors in the future.

Morgan vs. the Fed: In the late 1800's and early 1900's, J.P. Morgan had a reputation for very safe investments. Yet, in a bust, he also had the reputation of being a "lender of last resort". This means, when everyone else was in a panic, Morgan would make a rapid judgement of the assets of a firm and step in with money, if he thought he could profit from doing so. In comparison, when the government -- e.g. the Fed -- steps in, they are far less discriminate, and happy to save the unprofitable along with the good. By doing so, the government extends the duration of the recession.

Unemployment compensation: There was a time when workers formed union-like societies which helped in times of trouble: basically, offering various types of insurance. During a downturn, some of these groups would pay laid-off workers a stipend. If a large fraction of their members were laid off, these societies were often motivated to negotiate lower wages for all, if it meant more workers could be put back to work. Then, the government took over the unemployment-insurance business, and co-workers no longer had that incentive to accept lower wages. Once again, government intervention smothered emerging private solutions, and created a system where adjustments are long and drawn out.

A moral argument for soft-landings: Somewhat of an aside, but one can also make a moral argument that the government got the economy into the mess it is in and so it has a responsibility to help those whom it harmed. This is not an argument one hears from statists though; if it were, we be on our way to success and would only be discussing how best to transition.

Summary: Economist George Reisman uses the metaphor of a spring. As jobs, credit and businesses are "liquidated" during a downturn, and as their prices fall, they become increasingly attractive for investors. Government action -- by and large -- slows down the correction. By making the recession more shallow, the spring of attractive-valuations is not compressed enough, and the bounce-back is slower to emerge.

Example: Imagine two countries -- Redland and Blueland -- both with unemployment around 5%.

Next, imagine unemployment shoots up to 14% in "Blueland" while "Redland" has a far milder rise to 8%.

However, the rate of unemployment comes back to 5% much sooner in Blueland, while it lingers at a 8% for a while in Redland.

Is there any reason to think Redland is better off in this example? Even if we accept the notion that governments can and may engineer a soft-landing, it is far from clear that a shallower recession is a good thing, if it means extending its duration.

Think of individuals: Would you rather be unemployed for 1 year or for 3 years? It's a no-brainer! A laid-off dad from my son's school told me his savings could last him six months before he starts getting desperate. For him, a short sharp downturn would be softer. A worse rate of employment is the softer landing for the person who is unemployed, if it means a short unemployment. To some extent, those thinking about a soft-landing in the conventional way are committing a fallacy of composition.

Softer for some: The political support for soft-landings comes from those who think it will save their job or put them back to work. Imagine a company which is about to fire 10 employees due to budget cuts. Then, the government provides some type of aid and they only fire 5. The 5 who still have their jobs are pleased. Not just them: the 200 other employees in the company breathe more easily too.

Even the injured are positive: The 5 fired employees who will end up being out of work for longer -- because the wealth for the 5 "saved" jobs has to come from somewhere else -- are not pleased, but they often think positively about the soft-landing that "at least saved some jobs". Instead of being against soft-landings, they're the ones thinking the government ought to have done more. (If the government could work miracles by creating wealth out of thin air, why wouldn't they simply save each and every job lost anytime, anywhere.)

New reality: A bust happens when people around the economy change some very fundamental assumptions, and react to these changes. Finally, the economy will adjust to the new assumptions. Generally, the faster the adjustment, the better.

Panic vs. Adjustment: Even so, there is an argument for soft-landings which must be addressed. This is an economic argument that can be called "panic vs. adjustment", and it goes like this: it is true that the economy has to adjust and the sooner the better, but if this happens in a state of panic, it causes additional more damage. Take the example from above, of a company that was going to lay off 10 employees, but the government "saves 5 jobs". The argument would be made as follows: the panic has sent things below the point where they're finally going to end up. If the company fires 10 employees today, in a year or two -- when things are stable -- they will want to hire back 5. Why fire those 5 employees today and risk having them shift to some other occupation; then, hire 5 others employees in a year or two?

Vulture investors: There's an element of plausibility to the premises of that argument. Emotions run high in booms and in busts. Yet, in every boom, there are also some investors who hold back when they think optimism has run too high. During a bust, these people are happy to step in and put money into areas that they think are going cheap. Even a bankrupt company often has investors ready to pick up the pieces. In fact, since bankruptcy removes various legal obligations to pay its debts, a failing company becomes more attractive to buyers once it has gone through bankruptcy.

The government often touts the GM turnaround as a success, but it is no such thing. When governments attempt rescues, their eyes are on votes rather than profitability. GM would not have disappeared in a bankruptcy. Instead, it would have been owned by people who were formerly its creditors. Relieved of debt, the new owners would have invested in their assets. Instead, the government virtually ripped up the creditors' contract and gave the unions concessions. In doing so, they gained votes, but ended up with a company that is saved for now, but weaker than it would have been post-bankruptcy. By robbing the creditors, the government also makes it more costly for similar firms to borrow from creditors in the future.

Morgan vs. the Fed: In the late 1800's and early 1900's, J.P. Morgan had a reputation for very safe investments. Yet, in a bust, he also had the reputation of being a "lender of last resort". This means, when everyone else was in a panic, Morgan would make a rapid judgement of the assets of a firm and step in with money, if he thought he could profit from doing so. In comparison, when the government -- e.g. the Fed -- steps in, they are far less discriminate, and happy to save the unprofitable along with the good. By doing so, the government extends the duration of the recession.

Unemployment compensation: There was a time when workers formed union-like societies which helped in times of trouble: basically, offering various types of insurance. During a downturn, some of these groups would pay laid-off workers a stipend. If a large fraction of their members were laid off, these societies were often motivated to negotiate lower wages for all, if it meant more workers could be put back to work. Then, the government took over the unemployment-insurance business, and co-workers no longer had that incentive to accept lower wages. Once again, government intervention smothered emerging private solutions, and created a system where adjustments are long and drawn out.

A moral argument for soft-landings: Somewhat of an aside, but one can also make a moral argument that the government got the economy into the mess it is in and so it has a responsibility to help those whom it harmed. This is not an argument one hears from statists though; if it were, we be on our way to success and would only be discussing how best to transition.

Summary: Economist George Reisman uses the metaphor of a spring. As jobs, credit and businesses are "liquidated" during a downturn, and as their prices fall, they become increasingly attractive for investors. Government action -- by and large -- slows down the correction. By making the recession more shallow, the spring of attractive-valuations is not compressed enough, and the bounce-back is slower to emerge.

Comments

Post a Comment