The Great Degeneration - by Niall Ferguson

In "The Great Degeneration", Niall Ferguson argues that the west is stagnating because of broken "institutions".

The cause of Ascendancy: Ferguson rejects Max Weber's "cultural" explanation of a Protestant-driven industrial revolution. After all, the same root "culture" ended up in a very different East and West Germany or North and South Korea. While Jared Diamond's "geography" might explain why Eurasia was wealthier than the Americas, it does not quite explain the ascendancy of Western Europe. Finally, iIf genes are crucial, how to account for the gap between East and West German IQ scores, and how to explain why Eastern genes did relatively well until the last few centuries? The crucial factor, says Ferguson, is the socio-political institutions adopted in some countries: property rights, rule of law, and private voluntary organizations.

The role of Philosophy: He is right, but this explanation is incomplete: why did certain institutions develop in certain countries? Did human experimentation just happen to hit the right mix in England, or is there more? Even if the concretes of "the Protestant ethic" cannot get all the praise, there were important abstract ideas behind it. The key was the growing element of individualism. The preceding Renaissance gives credence to this more abstract version of Weber's thesis playing out in Catholic countries. Undercutting the role of church and monarch, and promoting the efficacy (and then the rights) of individual men, was a key movement that changed everything.

Critical Institutions: Ferguson thinks the British turning point came with the 1688 "Glorious Revolution" when the "rent-seeking", "extractive" elites -- the nobles -- began relinquishing power to newer elites. These new, non-hereditary elites were more inclusive; they needed and built institutions based on property rights. (Aside: Echoes of Rand's notion of an "Aristocracy of Money", replacing the old nobility. In George Bernard Shaw's play "Widower's House" we see denunciation of a slum-landlord, but the socialist author also shows regret at the way the nouveau riche can marry their way into the old aristocratic families.) Not surprising, though, that an aristocracy of money should engineer the creation of wealth. Even Whig wars, says the author, were waged less for glory than for profit. Ferguson praises the work of Hernando de Soto , arguing the importance of formal property rights. There is growing recognition that in some African countries, tribal-land, not yet allocated as individual property deeds, has held back development, invites corruption of tribal chiefs, and raises the importance of family and social ties relative to the ability to create wealth.

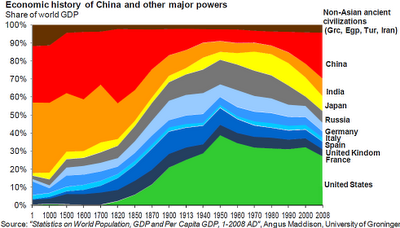

The East rises: Ming & Qing China did not experience the types of changes happening in the West, and Islamic law held back certain types of institutions. Meanwhile, the modern era began with colonialism replacing monarchical rent-seeking through extractive policies of its own. Post-independence elites imposed their own corrupt regimes, often breaking down even the good institutions of the colonists. Recently, non-European countries have recently been moving toward a rule of law. The process (from Paul Collier) is: reduced violence, property rights between citizens, checks on government, lower corruption.

The West stagnates: Meanwhile, says Ferguson, institutions in the west have weakened. The law (including regulation and licensing) has become overly intrusive and complicated -- law for lawyers -- ending up being a negative force. In addition, it pushes a uniformity of method that undermines variation and adaptive evolution. (Even in the private sphere, bureaucracy like ISO-9000 driven QA always results in lowered productivity. Add in "Sarbanes Oxley", Dodd Frank, environmental regulations, and the costs mount. We see Germany abandoning nuclear energy and the U.S. preventing the Keystone pipeline; just two examples of the purposeful retardation of wealth-creation that has become routine.)

Entitlements: Ferguson sees the high government debt-levels as an indication that the system is broken: with inter-generation inequity being a key problem. He muses on the irony of the younger generation supporting politicians who want to ignore the issue, rather than people like Paul Ryan (who at least talks about social security). Young people rose up in the "Arab Spring", and Ferguson wonders if young people will rise up in the West some day. (Actually, we have seen some of this in Greece, and perhaps a little taste in the U.S. "Occupy Wallstreet" movement and in the enthusiasm for Rand Paul.)

The way out: Can the west stop this process without first going through a big shock? Ferguson thinks the only alternative is if "civil society" institutions can once again increase their role in education, safety-nets, local projects. He thinks government involvement has lessened the support for such organizations and has made the system more fragile.

This short book is an easy read, and Ferguson seems to have the history right. Unfortunately, he does not really offer much in terms of predictions or solutions.

The cause of Ascendancy: Ferguson rejects Max Weber's "cultural" explanation of a Protestant-driven industrial revolution. After all, the same root "culture" ended up in a very different East and West Germany or North and South Korea. While Jared Diamond's "geography" might explain why Eurasia was wealthier than the Americas, it does not quite explain the ascendancy of Western Europe. Finally, iIf genes are crucial, how to account for the gap between East and West German IQ scores, and how to explain why Eastern genes did relatively well until the last few centuries? The crucial factor, says Ferguson, is the socio-political institutions adopted in some countries: property rights, rule of law, and private voluntary organizations.

The role of Philosophy: He is right, but this explanation is incomplete: why did certain institutions develop in certain countries? Did human experimentation just happen to hit the right mix in England, or is there more? Even if the concretes of "the Protestant ethic" cannot get all the praise, there were important abstract ideas behind it. The key was the growing element of individualism. The preceding Renaissance gives credence to this more abstract version of Weber's thesis playing out in Catholic countries. Undercutting the role of church and monarch, and promoting the efficacy (and then the rights) of individual men, was a key movement that changed everything.

Critical Institutions: Ferguson thinks the British turning point came with the 1688 "Glorious Revolution" when the "rent-seeking", "extractive" elites -- the nobles -- began relinquishing power to newer elites. These new, non-hereditary elites were more inclusive; they needed and built institutions based on property rights. (Aside: Echoes of Rand's notion of an "Aristocracy of Money", replacing the old nobility. In George Bernard Shaw's play "Widower's House" we see denunciation of a slum-landlord, but the socialist author also shows regret at the way the nouveau riche can marry their way into the old aristocratic families.) Not surprising, though, that an aristocracy of money should engineer the creation of wealth. Even Whig wars, says the author, were waged less for glory than for profit. Ferguson praises the work of Hernando de Soto , arguing the importance of formal property rights. There is growing recognition that in some African countries, tribal-land, not yet allocated as individual property deeds, has held back development, invites corruption of tribal chiefs, and raises the importance of family and social ties relative to the ability to create wealth.

The East rises: Ming & Qing China did not experience the types of changes happening in the West, and Islamic law held back certain types of institutions. Meanwhile, the modern era began with colonialism replacing monarchical rent-seeking through extractive policies of its own. Post-independence elites imposed their own corrupt regimes, often breaking down even the good institutions of the colonists. Recently, non-European countries have recently been moving toward a rule of law. The process (from Paul Collier) is: reduced violence, property rights between citizens, checks on government, lower corruption.

The West stagnates: Meanwhile, says Ferguson, institutions in the west have weakened. The law (including regulation and licensing) has become overly intrusive and complicated -- law for lawyers -- ending up being a negative force. In addition, it pushes a uniformity of method that undermines variation and adaptive evolution. (Even in the private sphere, bureaucracy like ISO-9000 driven QA always results in lowered productivity. Add in "Sarbanes Oxley", Dodd Frank, environmental regulations, and the costs mount. We see Germany abandoning nuclear energy and the U.S. preventing the Keystone pipeline; just two examples of the purposeful retardation of wealth-creation that has become routine.)

Entitlements: Ferguson sees the high government debt-levels as an indication that the system is broken: with inter-generation inequity being a key problem. He muses on the irony of the younger generation supporting politicians who want to ignore the issue, rather than people like Paul Ryan (who at least talks about social security). Young people rose up in the "Arab Spring", and Ferguson wonders if young people will rise up in the West some day. (Actually, we have seen some of this in Greece, and perhaps a little taste in the U.S. "Occupy Wallstreet" movement and in the enthusiasm for Rand Paul.)

The way out: Can the west stop this process without first going through a big shock? Ferguson thinks the only alternative is if "civil society" institutions can once again increase their role in education, safety-nets, local projects. He thinks government involvement has lessened the support for such organizations and has made the system more fragile.

This short book is an easy read, and Ferguson seems to have the history right. Unfortunately, he does not really offer much in terms of predictions or solutions.

Comments

Post a Comment